![]()

Ciudad de México

14 mayo 2005

![]()

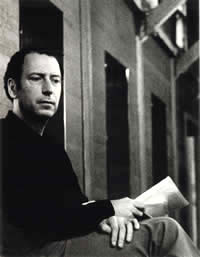

Mexico City - The Chilean poet David Rosenmann-Taub is considered a living legend. He resides in the United States far from the limelight; he is an enigma, like his poetry. In Chile, his latest published book is already out: País Más Allá (Country Beyond) (LOM, 2004).

Is a poet born or made?

Is a poet born or made?

“In my experience, the poet is born. But that is not enough. A spark is fragile; one must take care of it,” states Rosenmann-Taub, who dictated his first poems and learned to play the piano at the age of two, and who plans to bring out a book called Opus Uno (Opus One), with poems that he composed between two and fourteen.

His poetry, considered cryptic, was forged in his childhood. When he was born, on May 3, 1927 in Santiago de Chile, his family, of Polish origin – Manuel Rosenmann, a polyglot and reader of literature, and Dora Taub, a pianist – inspired him with a passion for art.

His youth and his family memories are present throughout his artistic work, as much in his first published book, Cortejo y Epinicio (Cortege and Epinicion), written during school recesses, as in País Más Allá, where his childhood is merged with those of his parents and grandparents.

What mark have your mother and your father left on your poetry?

“I’ve been very fortunate. Without the experience of my father and my mother, I wouldn’t exist. They were constant poetry in action. They didn’t speak unnecessarily: I have been able to confirm, over the years, that they only spoke to me with certainty. I cannot tell you that I remember my parents, in the same way I cannot tell you that I remember my arms. I consider myself the expression of them: their testimony. They were a lesson in non-prejudice. But my father warned me: ‘For better or for worse, some prejudices are correct, so don’t have prejudice against prejudices. Listen to them, and examine them.’”

Since his earliest days, Rosenmann-Taub has fused his poetry with music, “like the fusion of flesh and blood,” he says. He considers that a poem is expressed not only in written form, but also plastically, sonorously, or musically, so that he tends to work out his poems as musical scores or make pianistic poems.

I was God and I was walking without knowing it./ You, oh you, were my orchard, God and I loved you, the poet, described by his critics as a mystic, wrote at twelve.

As an adolescent he studied Spanish at the Pedagogical Institute of the University of Chile, where he also took courses in science and languages. He gave lessons in piano and literature to contribute to the support of his family.

“What is the purpose of consciousness, if we don’t have curiosity (what we call the need for scientific knowledge)? “The point is to absorb what you experience. Art is very important, but it is nothing compared to immediate experience. The texts or paintings or music of others don’t inspire me; what inspires me is my experience. The work of others can please me, if I recognize a proximity or an affinity with something I was searching for and that may be there to a greater or lesser degree. If it is not within my experience, all that has a very questionable value for me.”

What is a poem?

“In a literary sense: to express, with exactitude, in its own particular rhythm, a knowledge of which I can be sure. I use the visible to get to the invisible. I bare my thinking. In a transcendental sense, a poem is an object, or an act, well done, useful, and, of course, positive.”

You have said that to live is a challenge. Is writing poetry also a challenge?

“To say the truth with precision, with certainty, not to lie, as in a scientific investigation that has reached its ultimate consequences: that is a challenge. To accept the challenge is the real challenge. I don’t see a difference between science and poetry. The function of art is to express a knowledge in the most exact possible way; otherwise, it has neither function nor destiny. I came to the world to learn. If I don’t learn, I am less than nothing: I murder my time. It’s already a lot to know a truth, almost a utopia and, sometimes, a complete utopia. To express it constitutes the domain of true poetry.”

For Rosenmann-Taub, 1973 was marked by misfortune. To the coup d’etat against Salvador Allende was added the fact that he was robbed of almost all his poetic material (more than 5,000 pages).

Although he doesn’t elaborate upon his experience under the dictatorship of Pinochet, the poet does demand punishment for “the authors and those responsible for the horrors I witnessed at that time in Chile.”

The author of Los Surcos Inundados and Los Despojos del Sol emigrated to the United States twenty years ago, but he doesn’t see himself as an emigrant.

“The Earth is a single house. We live in a round house. Now I am in the dining room, later I will be in the bedroom. Did I emigrate from the dining room to the bedroom? I am on the Earth. I have not emigrated.”

You have said that to write for and to think about readers is to betray oneself. For whom do you write?

“It’s the same as asking a man of science: ‘For whom do you do research?’ When a woman gives birth, does she do it for society? Similarly, an artist gives birth to his work. When I write, I think about one reader, myself, who doesn’t have time to waste time.”

Why is it so difficult to gain access to you?

“If I were a doctor and had many patients who were weak and needed me urgently, would you ask me, ‘Why is it so difficult to gain access to you?’ When we gain access to a person who devotes himself seriously to an activity, we always interrupt him.”

What makes you happy? What horrifies you?

“Two contrasting questions. To be born and to be conscious is to be happy, of course, that you are happening. To be able to be happy, one must forget the horror. And, while suffering the horror, one must try to retain the happiness. Can one be happy today, having experienced a horror yesterday? Happiness and horror are, in reality, simultaneous. The only happiness that we can have is a horrendous happiness: that of knowing something, if indeed one can know something. To experience a horror, to enter into the greatest depth of that horror, is the happiness of knowing.”

Rosenmann-Taub says that he knows a lot about Mexico, “but not its territory;” he deems current the work of Alfonso Reyes, Mariano Azuela, Nezahualcóyotl, and has given lectures on Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz.

“Juana Inés de la Cruz is one of the best authors of Hispano-America. She imitates Góngora formally, but her orientation in Primero Sueño is quite different. Góngora is after plasticity: the static movement of nature: to create a picture by means of words. Juana Inés de la Cruz is after a conceptual picture. The imitation is stylistic, not one of content. She is the continuator of the Mexican culture virtually demolished by the Spanish conquest.”

Rosenmann-Taub would like his poetry to be published in Mexico. For now, it can be ordered from the publisher LOM by internet at www.lom.cl, or it can be read on the website www.davidrosenmann-taub.com. Since 2000, the nonprofit foundation Corda has devoted itself to the preservation and dissemination of his work.

“To publish a work is to protect it. I associate Mexico with Juana Inés de la Cruz. It would be satisfying to be published in the place where she lived. Primero Sueño began to be appreciated by Vossler and Pfandl in the 20th century. And the publication of her whole work is due especially to the efforts of Alfonso Méndez Plancarte. The evaluation of the significance of Primero Sueño is still far from what it deserves. Would you say that this work is only for initiates?”

Rosenmann-Taub is currently preparing the recording of his reading of País Más Allá and revising his book Poesietomía, which will be published this year by LOM, as well as En un Lugar de la Sangre.